Legacy Systems, Legacy People

This article has an IT bent to it. That’s because it’s what I know. But the idea of legacy systems and the long-in-the-tooth people who work within their frameworks also applies to teachers, nurses, public servants, and anyone else who’s stuck around long enough to be the one everyone calls when things stop working.

I once spent six hours trying to debug a critical failure in a system that turned out to be caused by a missing period in a 2,000-line COBOL program written in 1987 by someone who no longer worked with the company. There was no documentation. There were only comments in the code, sparsely scattered hither and yon, and even those were just blocks of code copied and pasted above the same code and commented out. (The English-like nature of COBOL, according to those who don’t need to debug it, is self-documenting.)

That, in a nutshell, is what it means to work with a legacy system.

Legacy Code

A legacy system, in the technical sense, is software or hardware that is outdated but still in use. It runs on older technology, often maintained out of necessity rather than choice. They are stable, reliable, and often essential. Think of a legacy system as being like a colonoscopy: nobody loves them, sometimes they’re a pain in the ass, but sooner or later everybody needs one.

And boy, do we need them. In fact, an estimate from 2022 suggests that there are about 800 billion lines of COBOL currently being used every day, worldwide. For some context, NASA estimates that there are between 100 and 400 billion stars in the Milky Way. That’s right - there are anywhere between two and eight lines of COBOL code in use right now for every star in our galaxy.

The bank that holds your accounts and investments? Legacy system. The Canada Revenue Agency that processes your tax return? Legacy system. Your ATM and credit card transactions? Legacy system.

Your school’s student records system? Legacy.

The scheduling software at your local hospital? Legacy.

That weird payroll platform that freezes if you click the wrong tab? Legacy.

The insurance company you called after hitting a parking lot light standard and watching it crash to the asphalt like a redwood in a logging camp — because six hours of debugging a system failure had left you incapable of safely operating a motor vehicle?* Legacy system.

They're not glamorous. They're not modern. But they work. Most of the time.

* – This did not happen to me. But it really did happen. Made a hell of a racket. Woke up one of the guys in the Research department who had been asleep since ‘93.

Legacy People

Whether you work in an IT department, a school, a hospital, or a government office - wherever - at some point, you go from being the enthusiastic new hire with fresh ideas to being the grizzled veteran everyone turns to when something breaks or that arcane scenario that only happens once every six or seven years crops up.

You're the one who knows which system records need to be rolled over and reset from one year to the next. Who knows where the backup tapes are and how to load them. Who remembers why there are ten lines of code in a subroutine that only executes for business years between 2006 and 2009. Who can make sense of a data dump when a batch job fails.

You become a legacy person.

A legacy person knows how to work within a broken system because they helped break it. Or at least, they were there when it broke. They're fluent in outdated tools, tribal knowledge, and the shortcuts and back-door fixes that were never supposed to be permanent.

Legacy people are often underappreciated. Until something breaks or someone forgets how to do something. And then, suddenly, you're a wizard again.

The Good and The Not-So-Good

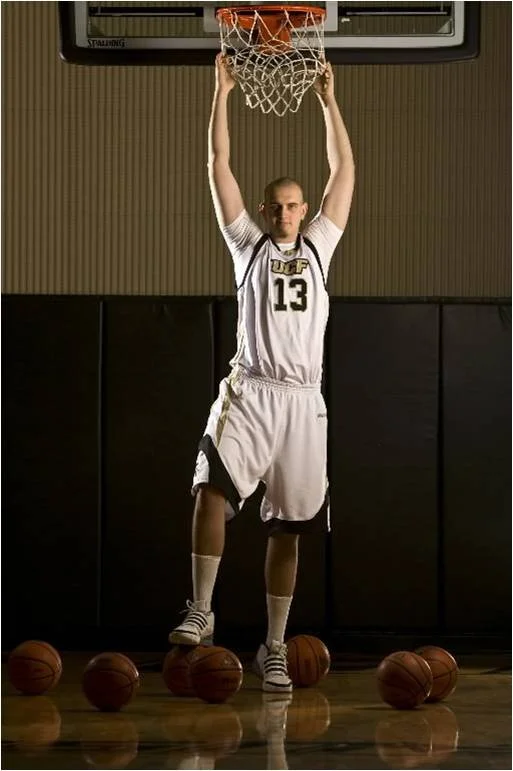

Being a legacy person is a mixed blessing. On the one hand, you have job security. On the other hand, you might also be the only one left who understands a system or process that absolutely nobody else wants to touch with a 7-foot pole.

Meet Jakub Kusmieruk, hailing from Sokołów Podlaski. At 2.23 m tall, he is a 7-foot Pole.

You become just like an old desk. You’re familiar. You’re reliable. You’re easy to overlook. And your drawers get stuck from time to time.

You watch from the sidelines as others move on to new roles with newer tools. They learn Python and cloud architecture and DevOps pipelines. Or they embrace the latest software, diagnostic tools, or frameworks. You're still running overnight batch jobs and praying they complete before 4 a.m. when the system is scheduled to shut down and restart. Then you pray that the system comes back online.

They’ve pitched a two-room tent and are kicked back in a camp chair, sipping cold craft beer from a solar-powered cooler while linguine boils and pancetta crisps in a carbon steel skillet over a propane flame.

Meanwhile, you’re in the site next door, smashing two rocks together over a pile of damp twigs while sitting on the mildewed tarp that will double as your blanket. Supper is a warm can of Dr. Pepper and the last third of a box of stale Triscuits you found under the car seat.

You get the idea.

Still Useful, Still Here

There’s real value in having people who know how to keep the old stuff running. Not everything needs to be modernized. Some things just need to keep working.

And legacy people aren’t just walking COBOL textbooks, or dusty program manuals, or outdated procedure binders. They know the organization. They know the patterns. They know the personalities. They know which meetings to skip and which printer to avoid.

They remember when the monitor on everyone’s desk was the size of a small diesel generator and had pixels in two colours: black and green. When the newly hired smart-mouthed whippersnapper who just called you Methuselah was still in diapers. When the mission statement was different. Hell, they remember when the organization didn’t even have a mission statement, and when people kept bottles of scotch in the bottom drawers of their desks just in case a party or a crisis broke out.

But It Doesn’t Last Forever

Eventually, legacy systems get replaced. Eventually, legacy people retire.

Sometimes they're pushed out during a reorg. Sometimes they leave on their own terms. Either way, the knowledge leaves with them. The workaround that never made it into documentation. The reason that a total on one report will periodically be out of balance with one from another report.

The company loses more than a body. It loses a memory.

Reflection

I really don’t think anyone, in any vocation, plans to become a legacy person. I know I didn’t. It just kind of happened. I can’t speak for anyone else in any other career, but for me, there was a certain comfort in knowing that my role (as straightforward as it was) and skillset (as antiquated and lacking as it often felt) would still be needed tomorrow. That my work was still challenging. That I was still able to provide tangible value in the form of helping the people around me. I kept showing up, kept solving problems, kept learning how things worked - until one day I realized that I finally had more answers than questions.

And I realized that what made me valuable (if I may be so bold) wasn’t just my knowledge. It was my context. It wasn’t what I knew, but why I knew it. I knew why things were the way they were. Even if I couldn’t always fix them, I could usually at least explain them. And sometimes, that was enough.

Sign Off

I may be out of the office now, but I still carry those systems in my head. The quirks, the hacks, the strange logic that somehow kept everything running.

And for what it’s worth, I did leave comments in my code.

Well… some of it.

And some of them were pretty darn funny.

Sometimes I’ll glance at the calendar and smile, thinking about the systems and reports that would’ve been (or maybe still are) chugging along at that time of year, quietly doing their job without much fuss or fanfare. It’s involuntary.

Spend enough time in a place and the calendar gets imprinted on your bones.

I imagine it’s the same for others who’ve been at it for decades.

Teachers, who still think in semesters, walk out the door with lesson plans that still work, a knack for calming down a room of thirty teenagers, and a mental map of which chairs to avoid in the staff room because they wobble.

Nurses, who instinctively track the rhythms of an emergency room, leave with a sixth sense for patient needs, a built-in clock for medication rounds, and insider knowledge of which snacks will be on offer based on who’s on shift.

Public servants, who live and die by budget cycles and policy rollouts, retire with a library of acronyms, an encyclopedic memory of government pivots, and the ability to write a 12-page memo that sounds like it says something, but doesn’t.

And all of them, all of us, leave with stories.

Like what you read? I write, rewrite, overthink, rewrite again, and eventually post these things in hopes they resonate. If you'd like to support the effort (or just bribe me to keep going), you can buy me a coffee. No pressure — but caffeine is a powerful motivator.

And full disclosure: you can’t actually make me buy a coffee with your donation. I might use it for a beer instead.